Have you ever been worried that the selfie you post might look bad? Or have you ever been anxious to know what others comment on your new post? The positive answers to both questions will not lead to a diagnosis of "social anxiety disorder", but may reveal some common phenomena in this digital age.

Though born as a homo zappien, I am always tired of maintaining self-image online, especially when involved in more and more different social media nowadays. Concerns for others' responses, as is described above, seem inevitable, therefore we turn to post different messages and news according to different groups of people we are related to on different media, which serves as an example of what Jan H. Kietzmann puts in his paper: the identity on a social medium is often aligned with the relationship on it. I remember, in Abby's first post for this class, she also talked about the distinction between her post on Facebook and Instagram. In her words, the one on Facebook was just an ordinary "I" while the one on Instagram showed the ideal image of "I".

Both the theory and our daily experience unveil the core element, identities, that distinguish our life online and offline. In the physical world, although we have to play different roles under different circumstances, the bound of space and time acts as a string that bunches all those "beads" to be a rosary. However, the possibility of multitasking provided by the virtual world breaks this congruity by presenting scattered scenes on various platforms, which results in our life online being fragmented and sometimes duplicated through presenting a lot of "I"s on different channels.

From my perspective, the current situation seems far from stable since the entropy and duplication of information we create is the symbol of the uneconomical use of computing capacity. As the phrase "social media ecology" used by Jan H. Kietzmann, will those social media merge together in a more unified form to enhance the resilience of this "eco-system" by taking better advantage of all the resources? I will wait and see.

No matter what the future holds, our attention is bound to be spared for keeping our voice on so many media. Hence, despite the dispute between Karpinski and Pasek over methods to study the correlation between Facebook usage and academic achievement, I always find that we will shut down our phones if we are rushing for the deadline. Moreover, it is definitely a cognitive interference if we try to check Facebook while doing homework since they both need to occupy the our visual channel. Thus, a trivial conclusion here is that irrelevant Facebook usage will negatively influence our work if we try to manage the two at the same time.

Whereas academic achivement is not just an one-off output. If we take Facebook usage as a broad term, apart from following the leader of an acedemic field or paying attention to the page of a research centre, even a relationship that is maintained on the Facebook may play a key role in our academic achievement one day, which is hard to be quantified and measured.

To be honest, I am not so interested in such a big topic on the correlation between Facebook usage and academic achievement for all people. Obviously, it is almost impossible to come to a general conclusion that everyone will agree on as people are so miscellaneous and so are the ways to use facebook. Maybe the best answer to this question would be two words, "it depends".

Wednesday, September 28, 2016

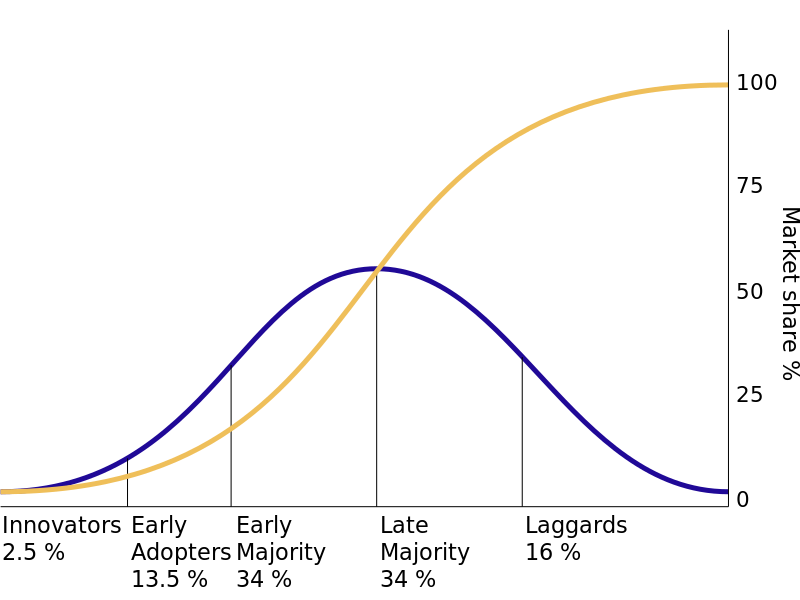

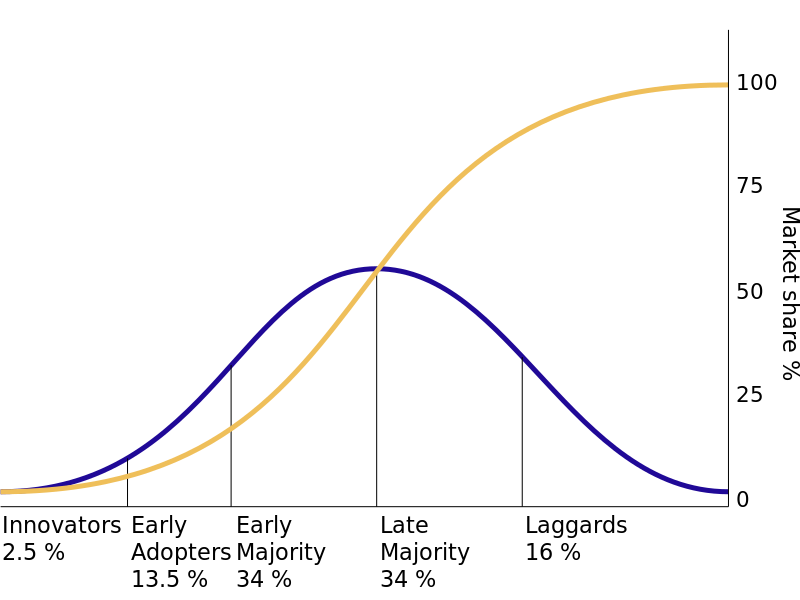

Appendix to Session 3 "The Diffusion of Innovations"

FYI, I pasted the curve of the old model, "the diffusion of innovations", I mentioned last time and the link to wikipedia below. While the model was first published in 1962 by Everett Rogers with regard to agricultural technology, it has already been adapted to its modern version to help us gain an in sight of how innovations permeate the society from "geeks" to "grannies".

Personally speaking, I am very fond of the theory like this that can lead us to think more about micro-mechanisms("capillaries rather than arteries") of how technologies affect our life day after day. Even a tremendous revolution cannot change people's ways of thinking and acting in a sudden. Neither will a burst of new technologies manage it. Hope to learn more about how those changes take place step by step since it will fuel my confidence in making a difference to the world we live in small ways that I can afford.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Diffusion_of_innovations#History

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Diffusion_of_innovations#History

Personally speaking, I am very fond of the theory like this that can lead us to think more about micro-mechanisms("capillaries rather than arteries") of how technologies affect our life day after day. Even a tremendous revolution cannot change people's ways of thinking and acting in a sudden. Neither will a burst of new technologies manage it. Hope to learn more about how those changes take place step by step since it will fuel my confidence in making a difference to the world we live in small ways that I can afford.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Diffusion_of_innovations#History

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Diffusion_of_innovations#History

Wednesday, September 21, 2016

MSTU4020: The Information Society

Having finished the readings for this session, I had a feeling that the world online was not much different from the world offline. It is human beings that matter rather than technologies themselves.

Although it seems a new challenge for us to engage and organize people in the cyberspace with the help of social media and websites, the underlying tactics and theories are rooted deeply in our attributes as social beings. For instance, the principle of Porter's Funnel does not only work offline but also shows its validity online through a variant of Funnel as the reader-to-leader framework in Preece and Shneiderman's paper.

What's more, there is no certain virtue or essence of the internet and other ICTs, despite the hope they have brought us of creating a communal area that endorses freedom and sharing. Just as Preece and Shneiderman put it, power of these technologies will also be taken by "hate groups, terrorists organizations, and deceptive corporations" with "malicious intent". Slander and libel will get their chance to spread at the same time when we improve our design to promote sharing of good ideas. The paper assigned last week, "technology as social practice", shared the same view in this aspect -- "technologies and social practices are mutually constituted".

Even if many disciplines culminates because of the increasing ability of analyzing big data, it is not sufficient to give evidence for "technological determinism" we discussed. As the slides, "six provocations for big data", present, the acceleration of data processing capability never automatically provides us with the right way to use it. Data do not necessarily entail accuracy and "bigger" is not equivalent to "better". It is still mankind that determines which model should be applied and how to interpret the outcome.

Therefore, it is us that consider our relationship with technology and change it if we want but not vice versus. Also, the introduction of new technologies never reforms the human nature as much as we imagine.

Tuesday, September 13, 2016

MSTU4020: A Response to A Question in Class

In last class, we were asked to discuss a question whether the machine was using us or not. Some said yes, some said no. But I had a feeling that this question seemed to be too rough to be answered. Neither "yes" nor "no" can express my complex attitude towards the question.

What is "us"? Apparently, there are at least two groups, creators and users, that have different relationships with the machine. Mostly, we regard ourselves as users when facing this question, therefore those high-tech machines are like black boxes to us. According to this presupposition, we are kind of afraid of machines because we have seldom ideas about how they work, just as the saying goes, "Fear is the by-product of the unknown." However, things will be much different from creators' aspect. They surely know mechanisms of gadgets they produce and will just take them as utensils for human.

Hence, I tend to think that the worry shown in the short video will fade away when we become more and more informed of the mechanism of the machine. (Just imagine the fear of lightning when people know nothing about electricity.)

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)